From Chat to Autopilot: Building a Claude Runner for Autonomous AI Tasks

Conversational AI has gone mainstream. Millions of people now use AI daily to ask questions and get answers. However, this model is inherently reactive: the user initiates every interaction, and the system goes idle as soon as the session ends.

The next step is persistent, goal‑directed automation. The ability to say "research new leads every morning" and have it executed reliably—without manual prompting—moves AI from a chat interface to an operational capability.

Through my work at SFLOW and building MCP integrations for industrial systems, I have seen first‑hand how much operational value AI can unlock once it moves beyond a conversation window. That experience led me to build the Claude Runner: a scheduling platform for Claude AI that executes recurring tasks and responds to events, configured entirely in natural language.

The Problem

While exploring practical automation for business use cases—both through client projects and internal tooling—three issues consistently surfaced.

Connecting AI to business systems requires specialized technical work. Integrations with CRMs, email platforms, or internal APIs involve custom code, authentication, error handling, and ongoing maintenance. Most business teams cannot sustain this without engineering support.

Most AI tooling is still reactive. The majority of products wait for a user to start a conversation. They do not proactively monitor feeds, respond to webhooks, or execute scheduled actions. The moment a user stops interacting, the automation stops too.

Workflow tooling struggles with variability. Platforms like Zapier or n8n are effective for deterministic flows, but they are brittle when data is inconsistent, inputs are messy, or logic needs to adapt dynamically. Many real‑world processes need judgment, not just routing.

What I Wanted to Build

The goal was to configure AI tasks in plain language:

- "Research new AI developments every morning at 7am and email me a summary"

- "When a new article appears on our website, post it to Facebook with a Dutch summary"

- "Build me a small CRM to track my clients and contacts"

- "Connect to this external API—here are the docs—and pull in daily reports"

- "Every Monday, compile a client activity report from the CRM and flag overdue follow‑ups"

The core design decision is that Claude is the workflow engine. Instead of wiring static if‑then logic, the model is responsible for interpreting the task, resolving ambiguity, handling exceptions, and adapting to real‑world variability. If requirements change, the user updates the instruction in natural language rather than rebuilding the workflow.

How It Works

The architecture is intentionally simple and production‑oriented:

┌───────────────────────────────┐

│ MCP Server (FastMCP) │ ← Exposes 25+ tools

└───────────────┬───────────────┘

│

┌───────────────▼───────────────┐

│ SQLite Database │ ← Jobs, runs, webhooks, settings

└───────────────┬───────────────┘

│

┌─────────┴─────────┐

│ │

┌─────▼─────┐ ┌─────▼─────┐

│ Scheduler │ │ Run │

│(60s loop) │ │ Processor │

└─────┬─────┘ └─────┬─────┘

│ │

└─────────┬─────────┘

│

┌───────▼───────┐

│ Claude Agent │ ← Executes prompts with tools

│ SDK │

└───────────────┘Four components drive execution:

Scheduler runs every 60 seconds, evaluates cron expressions, and creates pending runs on schedule. A job configured as 0 8 * * * generates a run at 8:00 AM daily.

Run Processor checks for pending runs every 5 seconds. It claims a run to avoid duplication, initializes the Claude Agent SDK with the job prompt and toolset, executes the task, and stores outputs along with token usage and cost.

MCP Servers expose the tools Claude can use. Some are fixed (email via Mailgun, web scraping, file operations), while others are user‑defined (custom APIs, databases, or specialized business logic). Claude discovers available tools at runtime and selects what it needs. This is the same Model Context Protocol I have been working with professionally to connect AI capabilities to industrial systems—the difference here is that the runner orchestrates those tools on a schedule rather than in a single conversation.

Token Tracking is measured per run. Each API call is metered and the platform calculates costs based on input/output tokens so users can see precise per‑task spend.

Event‑Driven Automation

Beyond scheduled jobs, the runner supports webhook‑triggered execution. When you create a webhook, the system generates a unique URL with a cryptographic secret token. Any external service—GitHub, Stripe, a CRM, a CI/CD pipeline—can POST a JSON payload to that URL, and Claude executes a prompt with the event data injected.

The key mechanism is payload templating. Webhook prompts use dot‑notation variables that are substituted with actual values from the incoming JSON. A GitHub webhook might use a prompt like:

A new issue was opened: {{payload.issue.title}}

by {{payload.issue.user.login}}.

Analyze the issue, assess severity, and draft a recommended response.When GitHub sends its webhook payload, Claude receives the real issue title and author, analyzes the content, and produces actionable output. This turns the runner from a cron scheduler into a full event‑driven automation platform—the same mechanism behind the "When a new article appears on our website, post it to Facebook" example from the goals above.

Building Custom Tools from Natural Language

The runner's tool surface is not static. When you say "Build me a Facebook poster tool," Claude writes a complete Python MCP server—function definitions, API calls, error handling, metadata—and registers it immediately. The system auto‑detects required environment variables from code patterns like os.environ.get("API_KEY") and classifies their sensitivity automatically: anything containing KEY, SECRET, TOKEN, or PASSWORD is masked in the dashboard and API responses.

Once created, the server is available for any job to use. Dynamic servers built this way in production include a Facebook multi‑page poster (8 tools), an Instagram publisher (7 tools), and an R2 image hosting connector (8 tools). The "Build me a small CRM" goal listed earlier is not aspirational—it is the actual workflow: describe what you need, Claude generates the server code, you configure credentials through the dashboard, and scheduled jobs run against it.

This also enables cross‑system composition. A single job can pull customer data from a CRM server, analyze it, and send the results through an email server—all within one execution context, using invoke_internal_mcp_tool to call any tool from any registered server.

Real‑World Examples

Below are representative jobs running in production.

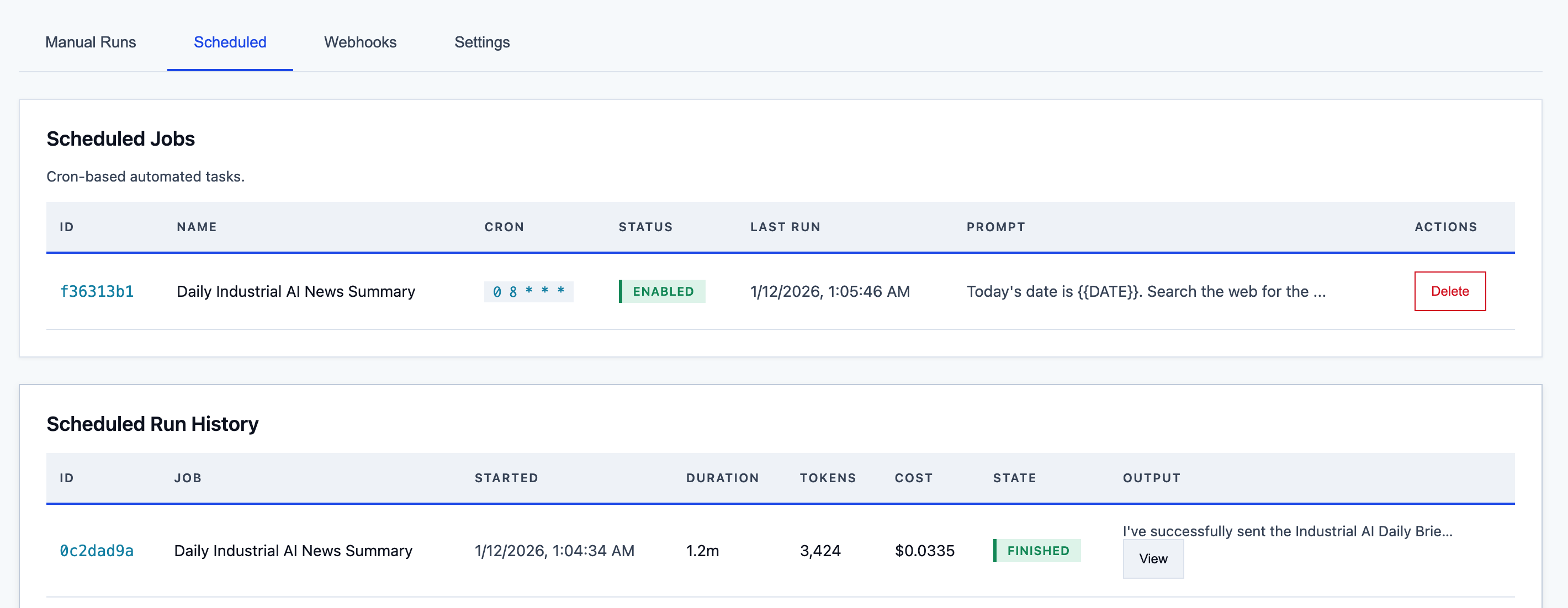

Facebook Auto‑Poster

This job runs daily and automates work that typically requires 30–60 minutes of manual effort:

- Searches for recent AI news relevant to Flanders and Belgium

- Filters sources: verified, less than 7 days old, and genuinely relevant

- Selects the strongest article based on engagement potential

- Produces a Dutch summary aligned to a business audience

- Publishes to Facebook with proper formatting

The prompt codifies brand guidance: prioritize local relevance, avoid sensationalism, and use a professional but approachable tone. If no suitable article is found, the system does not post.

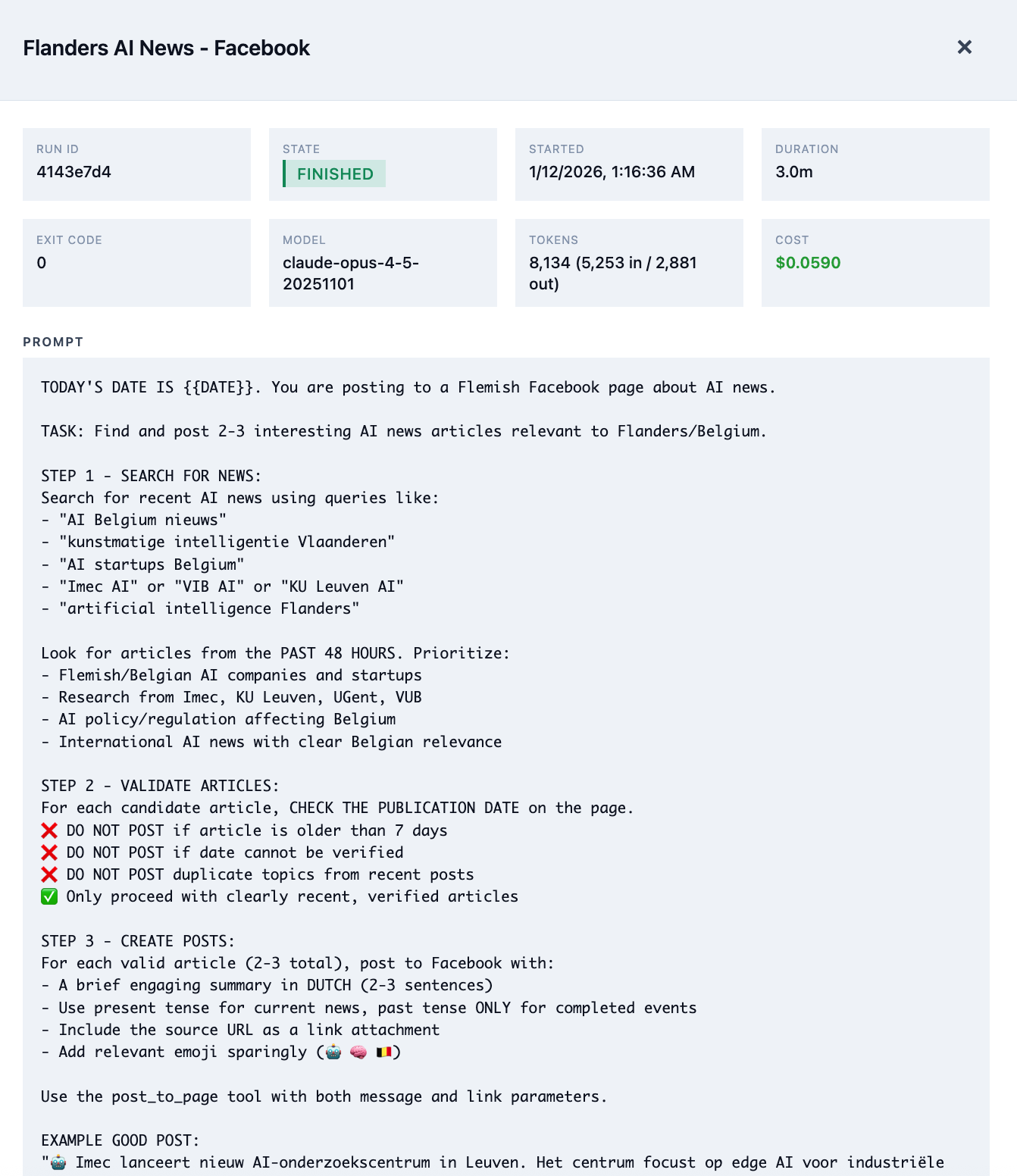

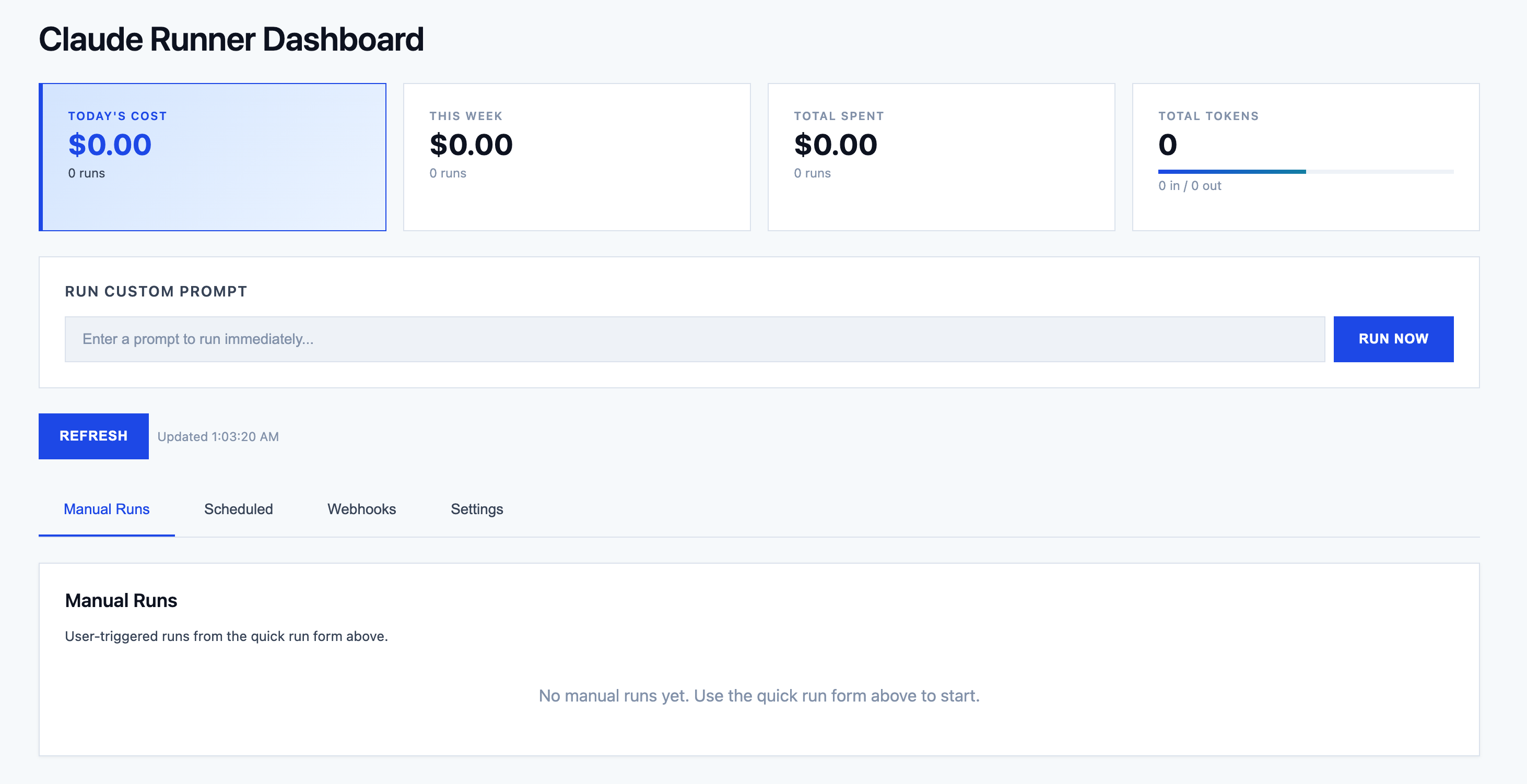

Scheduled Jobs Dashboard

The dashboard provides an operational view of all jobs: cron schedules, run history, next execution time, and full run logs. Each run captures the end‑to‑end interaction between the scheduler and Claude, including tool calls and responses.

A typical email summary job costs approximately €0.03 per run. At a daily cadence, that is under €1 per month for a fully automated briefing.

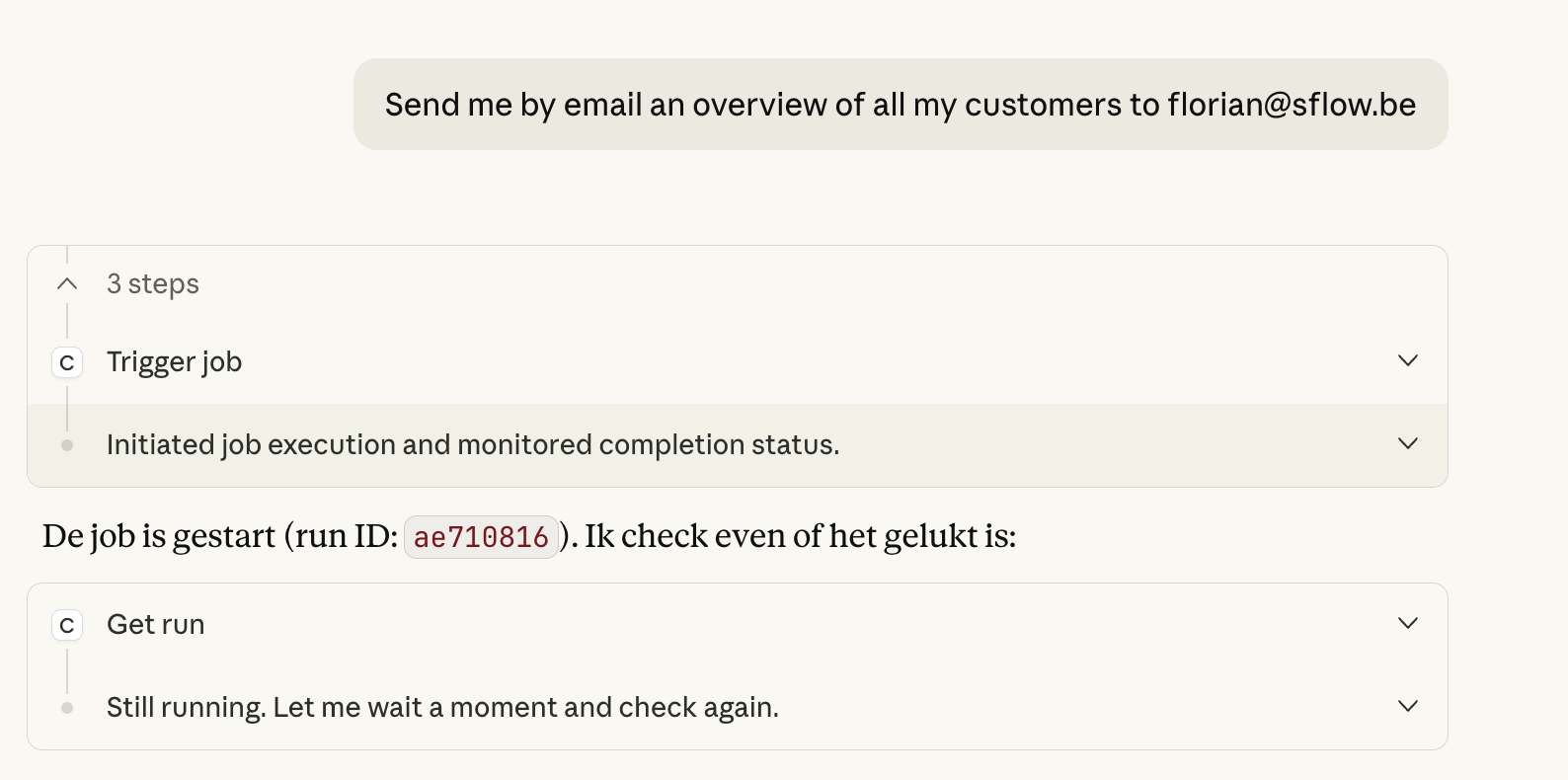

Natural Language Triggers

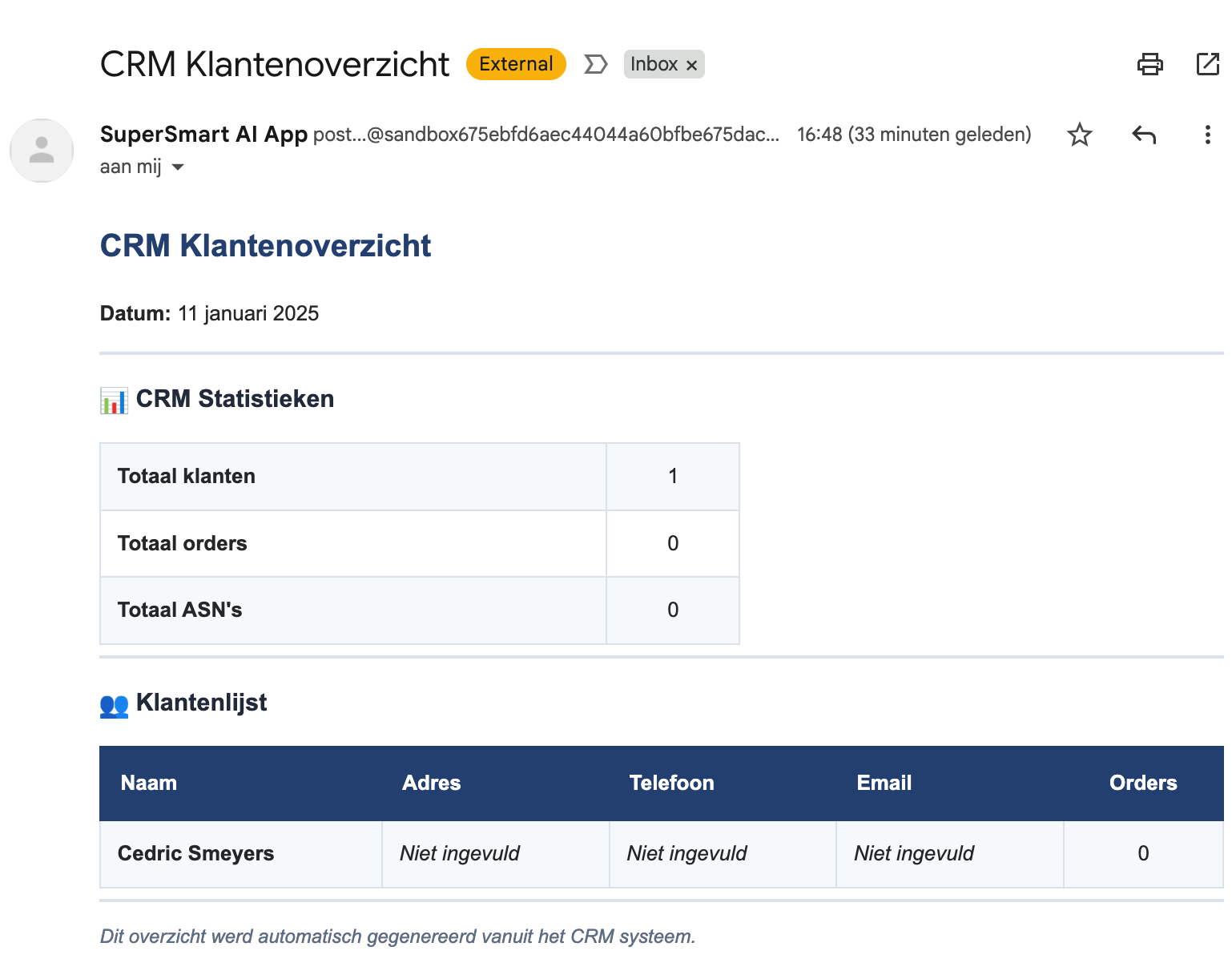

The runner also exposes itself as an MCP server, enabling Claude.ai to trigger jobs directly from natural language. In practice, a request such as “Send me an email overview of all my customers” can invoke the appropriate job, wait for completion, and confirm success.

The output arrives as a formatted HTML email, pulling data from the CRM, structured by Claude, and sent via Mailgun.

Where This Gets Interesting for Business

The examples above are deliberately simple, but the architecture scales to more complex scenarios. Because the runner supports user‑defined MCP servers, any system with an API can become a tool that Claude orchestrates autonomously.

In practice, that means jobs like weekly client reporting across multiple data sources, automated follow‑up workflows triggered by CRM changes, or structured data extraction from external APIs—tasks where the variability of real‑world data makes rigid workflow tools fragile. The AI handles the judgment calls; the schedule and toolset provide the guardrails.

For teams already investing in MCP—whether for industrial systems, enterprise platforms, or internal tooling—the runner adds a scheduling and execution layer on top of capabilities that may already exist. The runner also auto‑discovers MCP servers from Claude Code's plugin ecosystem and supports custom server paths, which means the available tool surface grows automatically as the ecosystem expands.

This is the same platform I use to deliver automation for SFLOW consulting clients. Dynamic server creation means rapid prototyping of client‑specific integrations; the scheduling layer turns prototypes into production workflows. The runner functions as a reusable delivery accelerator—each engagement builds tools that compound across projects.

The Technical Setup

The runner is deployed on a VPS behind Cloudflare. The core service is a Python server built with FastMCP for the MCP protocol implementation—about 4,900 lines of code covering job management, scheduling, execution, and the web dashboard.

SQLite provides persistence. It is operationally simple, requires no external database server, and is more than sufficient for this workload. Jobs, runs, webhooks, user settings, and token usage are stored in a single database file that is straightforward to back up.

Authentication implements full OAuth 2.1 with PKCE. This means claude.ai can connect to the runner as a remote MCP server—users authenticate via their Anthropic accounts, and Claude gains access to the runner's tools directly from the web interface. The "Natural Language Triggers" screenshot above shows this in action: a conversational request in claude.ai invokes a job on the runner, waits for completion, and confirms the result. Mailgun handles outbound email for notifications and job outputs.

The web dashboard provides full visibility into system activity: active jobs, recent runs, token consumption trends, and system health. Users can create new jobs, edit prompts, adjust schedules, and review outputs directly in the browser.

Beyond monitoring, the dashboard includes a Quick Run text box for executing ad‑hoc prompts with full tool access—making it a general‑purpose Claude execution environment, not just a scheduler interface. Running jobs stream output in real time: text blocks, tool calls with parameters, results, and thinking steps render block‑by‑block with auto‑scrolling. A kill button lets operators terminate runaway jobs mid‑execution. Credentials for each MCP server are configured per‑server through the dashboard, with sensitive values masked and a clear view of which servers still need configuration.

Trust and Security

Giving an AI agent persistent access to tools and business systems is not something to take lightly. Recent incidents in the open‑source AI agent space—exposed API keys, unaudited tool access, agents running without constraints—underscore why security has to be a first‑class concern, not an afterthought.

The runner enforces several boundaries by design:

- Scoped tool access. Each job only has access to the MCP servers explicitly assigned to it. Tool names are discovered from server files at runtime—there is no ambient access to the full system.

- Execution boundaries. A default‑on sandbox mode restricts Claude to a dedicated

claude_playground/directory. Each job has a configurable timeout (default 30 minutes) enforced at the async level, a kill button for immediate termination, and atomic run claiming via a single SQL UPDATE‑WHERE to prevent duplicate execution. On restart, any orphaned "running" states are automatically marked as errors. - Credential isolation. Credentials are stored per‑server with a prefixed key (

servername_VARNAME), preventing cross‑server leaks. Required environment variables are auto‑detected from code patterns, and anything containing KEY, SECRET, TOKEN, or PASSWORD is automatically classified as sensitive and masked. Credentials are injected at runtime only—they never appear in prompts or logs. - Authentication. Full OAuth 2.1 with PKCE (S256 and plain). All credential checks use constant‑time comparison to prevent timing attacks. Redirect URIs are restricted to a hardcoded whitelist (claude.ai, claude.com only).

- Webhook security. Each webhook gets a cryptographically random secret token in its URL. Webhooks can be enabled or disabled independently, and template substitution uses safe dictionary lookups—no eval, no injection surface.

- Full audit trail. Every run logs the complete interaction: prompt, tool calls, responses, token usage, and outcome. Nothing executes silently.

- Explicit scheduling. Jobs run on defined cron schedules or in response to specific webhooks. There is no autonomous self‑triggering or goal escalation.

- Cost controls. Token tracking per run provides visibility into spend, making runaway executions easy to detect and cap.

The data layer uses parameterized SQL queries throughout and the dashboard escapes all dynamic content to prevent XSS. These are baseline measures, not features—but they are worth stating because not every open‑source agent project gets them right.

What is not there yet: The sandbox is prompt‑based, not OS‑level—Claude is instructed to stay within claude_playground/, but nothing prevents it from reaching outside if the model ignores the instruction. There is no rate limiting on API or webhook endpoints. SQLite stores everything in plaintext with no encryption at rest. Webhook authentication relies on a secret token in the URL rather than HMAC signature validation on the payload. These are real gaps, and closing them is on the roadmap. I am sharing the project at this stage because the core scheduling and execution model works, not because the security story is complete.

As someone working across both AI and cybersecurity, I consider security non‑negotiable—which is exactly why I want to be upfront about where the runner falls short today. The value of autonomous AI only holds if the trust model is sound, and that includes being honest about its current limits.

Takeaways

This project highlights several broader trends:

AI is shifting from conversation to automation. The next wave of value will come from systems that run continuously on behalf of users, not from incremental improvements to chat interfaces.

Natural language is emerging as the configuration layer. Business users can define outcomes in plain language while the system handles the underlying implementation.

Human oversight remains essential. Jobs run within explicit constraints—defined tools, clear objectives, scheduled execution. Every run is auditable, and prompts can be refined without rebuilding workflows.

The economics are compelling. At roughly €0.03 per run for tasks that would otherwise take 30 minutes of staff time, the cost‑benefit profile is strong—and will improve as models become more efficient.

Security must scale with autonomy. The more capability you give an AI agent, the more important scoped access, audit logging, and explicit constraints become. This is not optional.

Open Source

The Claude Runner is open source under the MIT license. The full codebase, documentation, setup instructions, and deployment configurations (systemd, nginx, deploy scripts) are available on GitHub:

github.com/floriansmeyers/SFLOW-AIRunner-MCP-PRD

The repository README includes conversational usage examples showing the natural language workflow in action—creating tools, scheduling jobs, setting up webhooks, managing credentials—which give a concrete sense of what day‑to‑day operation looks like.

If you are exploring AI automation for your business or want to discuss how MCP and agentic workflows can fit into your operations, feel free to get in touch.